Vitta

c. 350

( Vitta, Uitta, Witta )

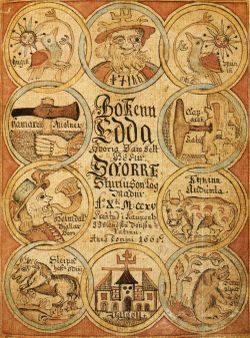

nother written source for the Witzel historian to consider is that of The Prose Edda, also known as The Younger Edda. �It was written by the Icelandic scholar and historian Snorri Sturluson around 1220. It survives in seven main manuscripts, written from about 1300 to about 1600.� �

�Snorri Sturluson (1178 - 1241) was an Icelandic historian, poet and politician. He was twice lawspeaker at the Icelandic parliament, the Al�ingi. He was the author of the Younger Edda or Prose Edda, which is comprised of Gylfaginning ("the fooling of Gylfe"), a narrative of Norse mythology, the Sk�ldskaparm�l, a book of poetic language, and the H�ttatal, a list of verse forms. He was also the author of the Heimskringla, a history of the Norse kings that begins, in Ynglinga saga with the legendary history, and moves through to early medieval Scandinavian history. He is also thought to be the author of Egils Saga.�

�As an historian and mythographer, Snorri is remarkable for proposing the theory (in the Prose Edda) that mythological gods begin as human war leaders and kings whose funereal sites develop cults (see euhemerism). As people call upon the dead war leader as they go to battle, or the dead king as they face tribal hardship, they begin to venerate the figure. Eventually, the king or warrior is remembered only as a god. He also proposed that as tribes defeat others, they explain their victory by proposing that their own gods were in battle with the gods of the others.� �

Snorri, in Nordic fashion, had committed to memory the sagas and folktales of his people. There can be no doubt that he was greatly influenced by the influx of Christian beliefs. As is true of all of the manuscripts that have survived, Snorri�s work shows a thorough Christian cleansing. All the same, it remains one of the most valuable sources available to the student of pre-Christian Nordic beliefs.

Our interest is in the Prologue of The Prose Edda, where Snorri tells of the migrations of the Saxon people. Written in Icelandic, it provides the Nordic spelling of the English name Witta:

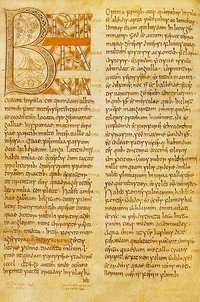

���inn haf�i sp�d�m ok sv� kona hans, ok af �eim v�sendum fann hann �at, at nafn hans myndi uppi vera haft � nor�rh�lfu heims ok tignat um fram alla konunga. Fyrir �� s�k f�stist hann at byrja fer� s�na af Tyrklandi ok haf�i me� s�r mikinn fj�l�a li�s, unga menn ok gamla, karla ok konur, ok h�f�u me� s�r marga gersamliga hluti. En hvar sem �eir f�ru yfir l�nd, �� var �g�ti mikit fr� �eim sagt, sv� at �eir ��ttu l�kari go�um en m�nnum. Ok �eir gefa eigi sta� fer�inni, fyrr en �eir koma nor�r � �at land, er n� er kallat Saxland. �ar dval�ist ��inn langar hr��ir ok eigna�ist v��a �at land. �ar setti ��inn til landsg�zlu �rj� sonu s�na. Er einn nefndr Vegdeg. Var hann r�kr konungr ok r�� fyrir Austr-Saxlandi. Hans sonr var Vitrgils. Hans synir v�ru �eir Vitta, fa�ir Heingests, ok Sigarr, fa�ir Svebdeg, er v�r k�llum Svipdag. Annarr sonr ��ins h�t Baldeg, er v�r k�llum Baldr. Hann �tti �at land, er n� heitir Vestf�l. Hans sonr var Brandr, hans sonr Frj��igar, er v�r k�llum Fr��a. Hans sonr var Fre�vin, hans sonr Uvigg, hans sonr Gevis, er v�r k�llum Gave. Inn �ri�i sonr ��ins er nefndr Sigi, hans sonr Rerir. �eir langfe�r r��u �ar fyrir, er n� er kallat Frakland, ok er �a�an s� �tt komin, er k�llu� er V�lsungar. Fr� �llum �eim eru st�rar �ttir komnar ok margar. �� byrja�i ��inn fer� s�na nor�r ok kom � �at land, er �eir k�llu�u Rei�gotaland, ok eigna�ist � �v� landi allt �at, er hann vildi. Hann setti �ar til landa son sinn, er Skj�ldr h�t. Hans sonr var Fri�leifr. �a�an er s� �tt komin, er Skj�ldungar heita. �at eru Danakonungar, ok �at heitir J�tland, er �� var kallat Rei�gotaland.�� |

From Arthur Brodeur�s 1916 edition of The Prose Edda, we have this translation:

|

�Odin had second sight, and his wife also; and from their foreknowledge he found that his name should be exalted in the northern part of the world and glorified above the fame of all other kings. Therefore, he made ready to journey out of Turkland, and was accompanied by a great multitude of people, young folk and old, men and women; and they had with them much goods of great price. And wherever they went over the lands of the earth, many glorious things were spoken of them, so that they were held more like gods than men. They made no end to their journeying till they were come north into the land that is now called Saxland; there Odin tarried for a long space, and took the land into his own hand, far and wide.' 'In that land Odin set up three of his sons for land-wardens. One was named Vegdeg: he was a mighty king and ruled over East Saxland; his son was Vitgils; his sons were Vitta, Heingistr's father, and Sigarr, father of Svebdeg, whom we call Svipdagr. The second son of Odin was Beldeg, whom we call Baldr: he had the land which is now called Westphalia. His son was Brandr, his son Frj�digar, (whom we call Fr�di), his son Fre�vin, his son Uvigg, his son Gevis (whom we call Gave). Odin's third son is named Sigi, his son Rerir. These the forefathers ruled over what is now called Frankland; and thence is descended the house known as V�lsungs. From all these are sprung many and great houses.' 'Then Odin began his way northward, and came into the land which they called Reidgothland; and in that land he took possession of all that pleased him. He set up over the land that son of his called Skj�ldr, whose son was Fridleifr; - and thence descends the house of the Skj�ldungs: these are the kings of the Danes. And what was then called Reidgothland is now called Jutland.� � |

This migration story is of some interest, but suffers in its historical accuracy. However, it reinforces the place that the name Witta/Vitta takes among the semi-mythological genealogies of the Anglo-Saxon people. In 1886, Viktor Rydberg suggested in his book, Teutonic Mythology, that Snorri adopted this information from an earlier English history. Ryberg�s remarks on this section of the Prose Edda are quite clear:

|

�The one branch has the names Veggdegg, Vitrgils, Ritta, Heingest. These names are found arranged into a genealogy by the English Church historian Beda, by the English chronicler Nennius, and in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. From one of these three sources the Edda has taken them, and the only difference is that the Edda must have made a slip in one place and changed the name Vitta to Ritta.� � |

Here Rydberg speaks of a transcription error in at least one of the surviving texts. And though Snorri�s genealogy changes the order of the line of Hengist, the text provides a written acknowledgement of the name in a Nordic tongue.

In comparison, Bede�s Ecclesiastical History of the English People offers the Latin version of the royal genealogy:

�Duces fuisse perhibentur eorum primi duo fratres Hengist et Horsa; e quibus Horsa postea occisus in bello a Brettonibus, hactenus in orientalibus Cantiae partibus monumentum habet suo nomine insigne. Erant autem filii Uictgilsi, cuius pater Uitta, cuius pater Uecta, cuius pater Uoden,�� � 'The two first commanders are said to have been Hengist and Horsa; of whom Horsa, being afterwards slain in battle by the Britons, was buried in the eastern parts of Kent, where a monument, bearing his name, is still in existence. They were the sons of Victgilsus, whose father was Vitta, whose father was Vecta, son of Woden; ...' � |

With the addition of The Prose Edda to the various English manuscripts (Gildas� De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, c. 540 �; Bede�s Historia Ecclesiastica, c. 731 �; Nennius� Historia Brittonum, c. 800; and The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, c. 890 �), a written understanding of the genealogy of the royal House of Kent provides the variations of Vitta and Uitta to the otherwise established name Witta. These variations occur as the language of origin changes, and also leads to the question of the development of the letter �W� in English and how it is pronounced throughout the Germanic regions.

Further inquiry relates the name Witta to an earlier pre-Christian view of the title �One who knows�. The later Anglo-Saxon concept of the Witan, or �the Council of Wise Men� finds its roots in an older tradition, most of which is based within Germanic oral tradition written down only in later years.

03-8-2006

� Home � Site Menu � Contact �