Georg Witzel

1501 - 1573

( Witzel, Wicel, Witzceln, Witzell, Wicelius, Vicelius, Wicelii, Vicelii, Vuicelio, Wicelio )

ery important to a study of the Witzel family name is the story of the life of Georg Witzel. He enjoys a certain following in Germany for his courageous stand during the turbulent times of the Protestant Reformation. With many writings on the �foundations of the Church�, Georg criticizes both the corruption in Rome and the extremists in the Lutheran movement.

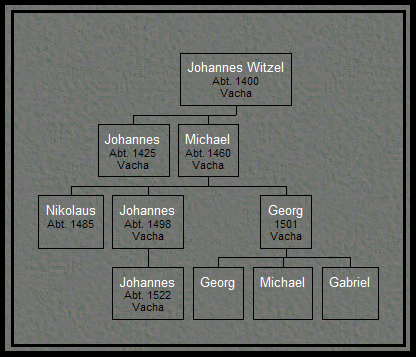

It is in Georg Witzel�s family history that the earliest history of the Witzel surname may rest. Because of his fame, Georg wrote a short commentary on the history of his family in Vacha. Later researchers have uncovered a great deal from records in Vacha and Fulda that extend the genealogy offered by Georg.

Georg�s grandfather, Johannes Witzel was known to own several houses in the Vacha region. Just how he gained such wealth is not known. But various wax seals used by the family carry the mark of the shoemaker�s trade. And occasionally, shoemakers could acquire a reasonable degree of wealth. Such a beginning could provide the funds for the owning of property and the profits that might follow.

Georg�s father was the owner of a tavern (Gasthaus) called the Zum Engel (to the Angel). It was in 1497 that Michael - Micheln, Michel - married his second wife, Agnes Landau of H�nfeld. In 1526, Michael headed the city council in Vacha. Certainly, Georg into a family that could offer him advantages.

Georg is known to have had a step-brother by his father�s first marriage, named Nikolas, and an older brother named Johannes:

Georg quickly advances his schooling with the support of his father. He attended schools in Vacha, Schmalkalden, Eisenach, and Halle before enrolling in a two year program at the University of Erfurt, at the early age of 14. Initially, he returned home to Vacha to serve as the local parish schoolmaster.

By 1521, at the age of 20, Georg again left home to further his religious studies, this time in Wittenberg. The University of Wittenberg was alive with ideas of reform. Many academics were bringing into question the unbearable abuses of feudal governance. Also at the University were the professors Martin Luther �, Andreas Carlstadt � and Philipp Melanchthon �. It is here, among this group, that the seeds of the Reformation first found fertile soil and launched Georg toward a future dedicated to rectifying the injustices of the Roman Church.

Georg again returned home to Vacha, in 1522. Here, he was ordained as an Augustinian priest. For a time he served as Vicar of Vacha, along with a short term as city clerk.

But by 1524, Georg had decided to abandon the Catholic faith. He moved to Eisenach and joined the Humanist movement and the debate for rights of all individuals before God. While in Eisenach, he married Elizabeth Kraus and began a family. The two would become parents to a total of eight children (Elisabeth, Anna, Georg, Michael, Gabriel, Katharina, Konkordia and Charitas).

It is here in Eisenach, that Georg became acquainted with the outspoken Jakob Strauss. Strauss led the criticism of the unjust practice of placing the poor in debt under false pretenses. Jakob and Georg saw the peasants as helpless victims of an unjust aristocracy. At Strauss' insistence, Georg began to preach in the small town of Wenigen-Lupnitz. From this pulpit, he spoke all the more loudly about the very evident need for religious reform.

Nearly all of Germany began to adopt the ideas of Humanists, of which Martin Luther is the best known. Starting in 1524, farmers began take action against those who treated them unjustly. This disturbance came to be called the Peasants' War or Farmer�s Rebellion. �

Some members of the establishment accused Georg of helping to excite the riots. In reality, Georg supported a non-violent expression of the new ideas. But it is possible that other members of Georg�s family were more directly involved. Regardless, the result was that Georg lost his post as a preacher in Wenigen-Lupnitz. Now without work, Georg was soon penniless.

Soon, Martin Luther came to his aid. With Luther's influence, Georg began preaching in the town of Niemegk. Renewed with enthusiasm, Georg became greatly involved with the writings of the humanist Desiderius Erasmus. �

Erasmus had made popular the writings of the early Church Fathers. He wrote about the need to maintain Church doctrine based upon classic and established principles. Georg, like Erasmus, now believed that reform could only be achieved by returning to the fundamentals of the early Christian Church.

In 1527, he approached the theologians at Wittenberg with his new found ideas. But Georg found no acceptance there. Instead, the Lutherans accused Georg of aligning himself with the Anti-Trinitarian views of Johann Campanus �. As a consequence, in March of 1530, he was arrested and imprisoned in the castle of Belzig. Ultimately, he was declared innocent and soon released. But the experience was greatly demoralizing to Georg. He returned to Niemegk. But now physically ill and greatly dissatisfied, Georg left the Lutherans, and resigned his position as preacher in Niemegk in 1531.

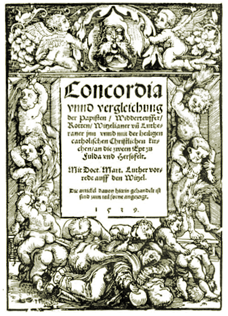

He and his family now returned to Vacha. Here, he openly spoke against the Lutheran sect. Once again, he was without a job and penniless. But Georg continued to publish, proclaiming the soundness of the humanism founded in Erasmus. He began to publish anonymously under the pseudonym of Agricola Phaqus. Even so, his identity was discovered when he released his Pro defensione bonorum operum in 1532. His statements brought the Lutherans bitterly against him. In 1533, he replied with the publication of his Apologia. This is considered to be one of his most significant works. Here he expresses his reasons for returning to the Church of Rome. � These writings brought him a new popularity through which he gained new friends. He now was invited to chair the new department of Hebrew language at the University of Erfurt.

For the most part, the aristocracy remained faithful to the power in Rome. Many were seeking a peaceful resolution to the current discontent. Thus, with his moderate view, Georg was invited by the Roman Catholic Count Hoyer of Mansfeld to serve as priest for the small conservative parish of Saint Andrew's in Eisleben. Here, George faced five years of bitter attacks from the Protestants Johann Agricola �, Justus Jonas �, and Balthasar Raid �. Georg later wrote of his experience in Eisleben: In Vacha, dogs barked, here howl the wolves... Despite these harsh attacks from his opposition, Georg continued to stand by his moderate view.

In 1534, he published Von der heiligen Eucharisty odder Mess (Of the Holy Eucharist or Mass). He spoke to the very question of Christianity, and the observance of the Last Supper. Georg openly brought a question to Luther:

|

Is Christ's Body and Blood truly present under the sacramental appearances? If thou art a Catholic, thou must say yes. Now then, is Christ's Body and Blood there a sacrifice also, and a victim? That is the crux of the question. But I will solve it for thee. If Christ's Body and Blood is no victim at all, then our faith is vain and we are yet in our sins. But if His Body and Blood is a victim even as yesterday so today, yea and for ever, how then darest thou deny Him to be a victim in the Sacrament? |

|

n August of 1538, Georg was invited to Dresden by George the Bearded, Duke of Saxony, to assist in reaching a compromise between the distancing factions. Under the protection of the Duke, Georg was able to speak freely against a radical resolution. But upon his benefactor�s death, Georg was forced to flee to the mountains of Bohemia in fear of his personal safety.

For a short time, he found protection under Joachim II, the Margrave of Brandenburg. But by this time the Reformation had gained its full force. Georg fled again, finding support for his ideas for a brief time in Lusatia, Silesia, and Bamberg.

Finally, in 1541, Georg returned to the security of his family home in Vacha, finding a safe haven with Abbot John of the Fulda Abbey. From here still, during the Schmalkald War, � he was forced to flee twice again, each time to Wurzburg.

After the long struggle, as he had narrowly weathered the hate, threats and adjustments that so controlled his life, Georg made his final move to Mainz in 1553, with his wife, Elisabeth, joining him in 1554.

Upon the sudden death of Elisabeth, Georg again focused his energies on writing. In 1564, he wrote his Defensio Ecclesiasticae Liturgiae. In this work, he speaks of the authority to be found in the �� consensus, of the first five centuries. � How much safer to use the old form . . . Nothing has been removed; the Lord's Supper is put into a better light by the auxiliary ceremonies, and the older they are the more sacred they are.�

In 1559, he received an imperial appointment under Emperor Ferdinand I. Here, he was granted a Doctorate of Theology. Despite being so greatly honored, Georg felt with deep regret hid disappointment that he was not able to successfully bring harmony among his religious colleagues.

I was on February 16, 1573 that George Witzel died in Mainz. Here, he was truly held in high esteem. Part of the inscription on his grave reads Our German Church owes much to him. A later historian adds an honorable note: If the Church had had more � Witzels, there would not have been the need for a Luther or a Calvin.

Georg is credited with having written nearly 140 works. As his humanist mentor, Erasmus, he felt that all questions of the salvation of the soul could be found in the Holy Scripture, without the interception of the Pope or the selling of indulgences. Thus, he believed that the Church had an obligation to provide sound doctrine that justly balanced the rights of all individuals before God.

Much can be learned about the early history of the Witzel family surname through a study of the family of Georg Witzel. In his letters, Luther referred to Georg as Wicel. And Georg's many wittings were published with many versions of his name: Jorge Witzel, Jorgen Witzceln, Georgio Witzell, Georgius Wicelius, Vicelius, Georgii Wicelii, Georgii Vicelii, Georgi Vuicelio, and Georgio Wicelio.

09-06-2006

� |

Ditzel, Olaf. 'Georg Witzel - erst Weggef�hrte, dann Gegner von Balthasar Raid'. Mein Heimatland. Band 39, Nr. 8. August, 2000. � |

� |

Ditzel, Olaf. 'Georg Witzels Vorfahren in Vacha'. Fuldaer Geschichtsbl�tter. Nr. 74. 1998. pp. 77-104. |

� |

Schroeder, Joseph. 'Georg Witzel'. Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved on September 6, 2006: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15680a.htm � |

� |

Richter, Dr. Gregor. 'Die Verwandtschaft Georg Witzels'. Fuldaer Geschichtsbl�tter. Nr. 8. August, 1909. pp. 113-126, 129-144, 155-160. |

� |

Rummel, Erika. 'A Review by Erika Rummel of Aus Liebe zur Kirche Reform: Die Bemuhungen Georg Witzels (1501-1573) um die Kircheneinheit by Barbara Henze'. Renaissance Quarterly. December 22, 1998. georg_review.html. � |

� |

Witzel, Georg. Genealogion quoddam Georgii Wicelii. 1557. pp. 1-4. |

� Home � Site Menu � Contact �